A lawyer friend of mine, who is also a Vietnam Veteran, had acquainted me with Lance Woodruff and provided an introduction for me. This legendary figure is world famous not only for his fifty years of humanitarian labors in both Viet Nam and Asia, but also for his stunning and haunting photography. So I emailed Mr. Woodruff that I would like to meet him and I invited him out to lunch.

"Come on out and meet me," he responded.

One sunny afternoon I drove west out Highway 90 beyond Cleveland, turned up the Number 252 ramp, north toward Lake Erie, and then turned right along the two lane road running beside Lake Erie to meet him at a home where he was staying.

Naturally with my two blind eyes I missed the side street where he was living, passed it by, and then perilously u-turned my black Lucerne Buick car to come back. But I missed his street again, had to execute another unsafe u-turn, but finally found the right avenue.

When I drove up to the house, I spotted a figure, short, paunchy, and with a scarf around his neck. This must be Photographer Woodruff. I stop in the driveway and roll down the side car window. "Mr. Lance Woodruff?" I call out.

"Yes," the figure answers and I open the car door from the inside. He laboriously pulls himself inside the front right seat.

As we drive away, he has already picked our lunch place. It is "Cravings," a Thai food restaurant, operated by a Thai Business woman. "Great," I announce, having never been there before, but generally liking Thai cuisine.

"By the way," I continue, "you have to tell me exact driving directions on the road because my eyesight is very poor. It seems as though the Good Lord always send us some sort of gift as we get older. So my challenging handicap is ever worsening eyesight. I guess if He loves you a great deal, then He sends you even more such illnesses and gifts."

"Is that so?" Lance slowly replies to my sad joke. Later, after I heard of his serious illnesses and burdens, I would regret my attempts at elderly humor.

We do miss the restaurant turn off from Lake Road the first time, but we turn around, drive back, and find the proper parking area. Seated inside, we search the offerings on the Thai menu. We choose the soup and a mainstay entree dish. Our food ambassador is named Tyler. "The cook," reports Tyler, "has to know how spicy you want your Thai food. We have a scale from 'one' which is very mild, all the way to 'ten' which is burning spicy hot. You get your pick."

Perplexed I look at Lance. "What should we choose?" I give Lance the first option. "I can go all the way to 'ten,'" he laughs.

"I worry '10' may be too much for my stomach, even '7' or '8' may be over my limit." "Okay, we can compromise," Lance kindly says.

"All right," I turn to Tyler, "We will settle on a concession of '6.'" Tyler nods yes, smiles at my cowardice, marks his small notebook, and heads for the kitchen in back.

"How did you ever get interested in Viet Nam," I open the interrogation. I always wonder how people learned about this small country and what is their particular interest. Their answers help me to know how to tune into their particular wave length. Having returned some thirty times to Viet Nam and buried deep in my historical curiosity about Dien Bien Phu, I now refrain from embarrassing others with my comments.

"Are you originally from Ohio?" he avoids my question. "Yes, my Father's family in the beginning had settled in Salem. Dad came to Cleveland, married here, and I have lived all my life in Ohio.

"Salem? That's odd," he remarks. "You know Highway 45, and then 59? That is in Lisbon, near Ravenna. Actually I consider Salem as my home area." "That connects us," I summarize. "because I think of Salem as our family home."

A pause. Lance does that a lot. Between paragraphs of conversation, he takes these momentary pauses, as if searching for something in his memory. Or is he weighing how much he should reveal to judgmental strangers.

"So you want to know how I got interested in Viet Nam?" Lance asks. "It goes all the way back to the famous battle at Dien Bien Phu in 1953 and 54. Our teacher had brought a radio into our history class and played the news accounts about this battle. Then I read about it while scanning the newspaper, laying on the front room floor."

So I picture a very young Lance laying on his stomach in his front living room holding his head in his hands propped deep into the carpet and reading the newspaper about Dien Bien Phu. Later after googling "Woodruff," I came across Lance's confession on what brought him initially to Viet Nam.

[The]Media coverage of Dienbienphu, God, Russian literature and the Spanish Civil War were part of my reason for going to Saigon as a 23-year-old photojournalist.

I admired Hungarian photojournalist Robert Capa who had died in northern Vietnam in May 1954. As an 11-year-old schoolboy in Ohio I listened to radio broadcasts of the siege of Dienbienphu in my grade six classroom and believed that civilization would essentially come to an end if 'the Viets' were victorious over the French. [These Viet's were the Viet Minh Communists as opposed to the many Vietnamese non-Communists including the Vietnamese National Army who were allied with the French Expeditionary Forces.]

All of this I could sympathize with for these echoed my experiences as well. I had been an eleven-year-old boy following the accounts of the battle in the morning newspaper. I would lay the paper out on the bed spread and trace the tiny lines on the front page picturing the Viet Minh trenches slowly but inexorably squeezing the life out of each French fortified hill. How painful it was when we received word about May 8, 1054, that the gallant defenders had ceased resistance and the Viet Minh Communists had won.

Of course, I had to go to Viet Nam and I even asked the Army (to whom I owed a six-year mix of active and reserve duty from my ROTC commission) to send me there where I wanted to work in the rural villages helping people. Eventually the Army gave in to my entreaties, but I would not work in the villages as I requested. I was a great believer in Dr. Martin Luther King's philosophy of Non-violence. "We can't have you," said the Executive officer of the Plei Ku Special Forces "B" team, who assigned newcomers to their slots, "running around in the Montegnard villages preaching your gospel of peaceful co-existence." SF recruited its native soldiers from these villages to battle the Viet Cong, whose training would stress bloody aggressiveness rather than brotherly love.

The Thai food arrives at our table and we split the main dish. "What," I queried Lance, "was your initial work in Viet Nam?"

"I worked for a religious organization, toiling on their charitable projects. I lived in the home of a Vietnamese Family. They were very Catholic and I of course was a good Presbyterian. I do not know whether it was their influence, but I moved from Presbyterianism to being a Good Methodist. Now I am on the border of Catholicism. We shall see what further spiritual adventures I entertain." Lance said this with a twinkle in his eye which betrayed the very spiritual aspects of his character. Of course, I love spiritually minded people and consider myself to be spiritual though I wonder off into worries about how much did Christ drink and did He ever take His name in vain..

"What was the background of this family," I asked.

"They had escaped from the North originally in 1954 because they did not like the Communists. [Another family saved by my hero, General Edward Lansdale, I mused. Too bad we betrayed Lansdale's wisdom on how to deal with Communist insurgencies!] Later in 1975 they would flee to the United States. The man did get his medical license in the United States. He has been practicing all these years and has done very well. His children have also prospered."

"That is quite an accomplishment," I state. "Even though he was a doctor in Viet Nam, in the US he almost has to start all over again to gain a medical license. There are also the language and cultural barriers he must have had to overcome. Has he ever gone back to Viet Nam?"

"No," says Lance. He has little interest in doing that.

I always urge people that they should return to their Vietnamese Motherland, for many reasons. In some way, I feel very invested in Viet Nam, especially Dien Bien Phu where I even think of settling. We Americans have paid much blood from all of our soldiers and others to earn a share of the Vietnamese land. Enough of that!

Lance Woodruff

Our luncheon conversation turns to Lance's personal War experiences which seem exceptional and miraculous.

"In 1966," Lance relates, "I had to travel by road from Da Lat to Sai Gon. Our vehicle was stopped by some government soldiers and they insisted I join them. So we spent a nice afternoon, swapping stories and drinking at a near-by café. One of them told me he had been with the French at Dien Bien Phu." [Not many know that the French units themselves at Dien Bien Phu were about half Vietnamese. That does not even begin to count the many Vietnamese soldiers in the VNA forces nor all of the native Thai and other minority groups populating the anti-Communist forces.]

"It was very fortunate," Lance stated, "that they had urged me to join them. Later I learned that the bus I had been travelling on was stopped further along the road by the Viet Cong and I surely would have wound up as their prisoner, or even executed by them."

Lance has a second story about a miracle escape: "Another time we were aboard a plane eventually bound for Savannakhet in Laos. "We were just getting ready to take off to stop at Ban Me Thuot. The plane, however, had a problem. We could not take off that day. The next day, the plane developed an engine problem. So we could not depart that evening. On the third day we were finally able to leave. When we arrived at our destination, we found the enemy had attacked the night before and all my friends I was to meet had been killed."

Lance has a third wondrous tale. "At one time of TET," he narrates, "I had made plans to spend this wonderful holiday with my friends in Hue. Eighteen of my Vietnamese friends and their family had gathered for the usual grand festivity for this New Year. Unfortunately, I got delayed and could not join the family celebration that day. The year was 1968. This was the beginning of the notorious TET offensive. The North Vietnamese soldiers assaulted into the city and came to my Friends' celebration. One of their sons was with the NVA. He betrayed all of them as South Vietnamese government officials. All eighteen were taken out by the NVA and butchered." [They joined the other 3,000 civilians massacred in Hue by the Communists during that TET.]

"Why did the son do that?" I asked. "He was with the enemy," Lance shrugged his shoulders. "Who knows the whole story?"

"You know," I explain my view of the TET offensive, "TET was always supposed to be an annual time when everyone in Viet Nam, including the soldiers on both sides of the war, went home to be with their families. There was an unspoken truce. Nobody was to conduct any attacks against the other side. So the Communist TET attacks were actually a betrayal of the truce. I never see this mentioned that way by the media in America nor by the peace activists. They say the Viet Cong took 'advantage' of this truce. But actually it was a form of treachery. Can you understand why the South Vietnamese never felt they could trust their northern brothers? Again I never see this in our history books." {And while our books quite rightfully recall the murders of almost 600 Vietnamese, including women and children by U.S. soldiers at My Lai they scarcely mention Communist atrocities including the killings of 3,000 at Hue. I am not condoning My Lai, but simply requesting that all such slayings are equally damned.]

Lance has had many assignments during his fifty years in Asia which included not only Indochina but Thailand and Burma as well. He worked on golf course projects near Ha Noi. He spent much time with the Western journalists including Bernard Fall, author of the number one history b

ook about the battle at Dien Bien Phu, entitled, "Hell In A Very Small Place: The Siege Of Dien Bien Phu ." [Would that every general and soldier in the American military had read this book before landing at Tan Son Nhut Airport or Cam Ranh Bay.]

." [Would that every general and soldier in the American military had read this book before landing at Tan Son Nhut Airport or Cam Ranh Bay.]

Lance even wound up as an Editor in Chief of an English language newspaper in Bangkok. He also casually mentioned he had worked for "several secret agencies" active in Asia.

Now Lance's life has slid into a series of ruinous health problems and constant operations. He referred briefly to these burdens.

When he has to leave our lunch table for several painful journeys to the restaurant bathroom, I think of poor Jesus climbing toward Mount Calvary. I really regretted my earlier witless banter in the car about God's gifts. I am waiting for my own crucifixion which I have thought of escaping by jumping in a parachute over the battlefield in at Dien Bien Phu. I think of the courageous French and Vietnamese soldiers even on the last night of the battle who jumped from their airplanes to float down through the enemy rifle firing at their white canopies. Their reward would be capture, forced three hundred mile marches through the jungle, imprisonment in disease-ridden camps, and even death from the Viet Minh mistreatment.

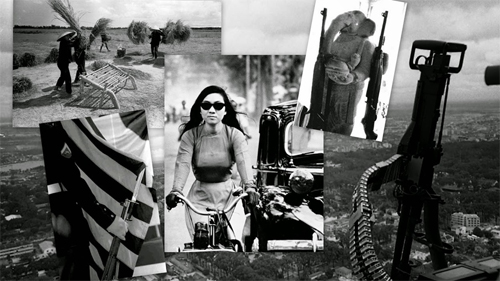

Lance's current dreams? He has a family that he loves and strives to support. For Viet Nam and Asia, he very much wants to publish a book of his best photographs as a tribute to all the peoples he has met. I have included parts of some of his photographic work below. I have also included some google items about Lance.

These begin with a description of him:

Lance Woodriff: Bangkok-based photo-journalist, editor and writer Lance Woodruff (Macalester College Class of 1964) posts this contribution as an artist, friend and long-time veteran war and Southeast Asian correspondent, and now as self-assessed 'veteran of the war.'

Here are more of his encounters with Viet Nam. Lance is writing:

In San Francisco in 1986, nearly 20 years after leaving Vietnam in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive, I learned and finally accepted that I was a veteran of the war.

…... …… By the time I arrived in Saigon in 1966 with two Pentax Spotmatics, a 6x6 Bronica and an Uher tape recorder the size of a small suitcase filled with bricks, I imagined myself as Leo Tolstoy's Pierre in 'War and Peace'. I thought that I would document war and its aftermath, walking around the edge of battlefields after the shooting was over, and that I would describe it, photograph and publish it, and

then we would all stop doing these things to each other. I would write the great American novel. I imagined that war could be solved.

On a combat mission in an American A1E fighter-bomber over the Ho Chi Minh Trail west of Pleiku, however, I looked death in the face and saw nothing pretty about it.

I simply understood that I would die. Repeated dives against three anti-aircraft positions plus soldiers on the ground shooting at my aircraft filled the air with tracers. I shot back with my cameras, blindly.

On that flight I carried two items, a small leather bound King James Version of the Bible and a typed copy of 'Monte de El Pardo' by Spanish poet Rafael Alberti.

In Vietnam I saw death and understood something about the taking away of life and the future for women and men, for children of any age. In peacetime one prepares for a future that does not usually mean the daily approach of death. Journalists are witnesses. When one has witnessed much, there is a responsibility to share what it means, or might mean. Looking forward to the new year I survey the year past, of memories shared with journalists from many countries.

What does have meaning? What does matter? What is the value of a life? One example comes to mind, Phung thi Le Ly, a peasant child in Quang Nam, was born a sickly two pounds-so small that her midwife wanted to kill her immediately. "Suffocate her!" the midwife told Le Ly's mother, Tran thi Huyen. Born to a middle-aged mother at work in the rice fields when her water broke, the child wasn't expected to live.

Her mother refused to follow traditional wisdom regarding "runts," and the infant survived, earning the nickname "Con Troi Nuoi", [which means] "child nourished by God."

Today Phung thi Le Ly carries small libraries and medical services and training to the rural people of Quang Nam. Rock on and practice peace and love.

Top of Page

Back to Joe Meissner Columns